| Terrace of Pride

Encounters: Proud Penitents. Cantos 10.100-39, 11.1-142 Allusions: Whips and Bridles. Examples of Humility and Pride. Cantos 10.28-96, 12.13-69 "VOM" Acrostic. Canto 12.25-63 Cimabue -> Giotto Guido Guinizzelli -> Guido Cavalcanti -> ? Canto 11.94-9 Gallery Audio Study Questions Home |

|

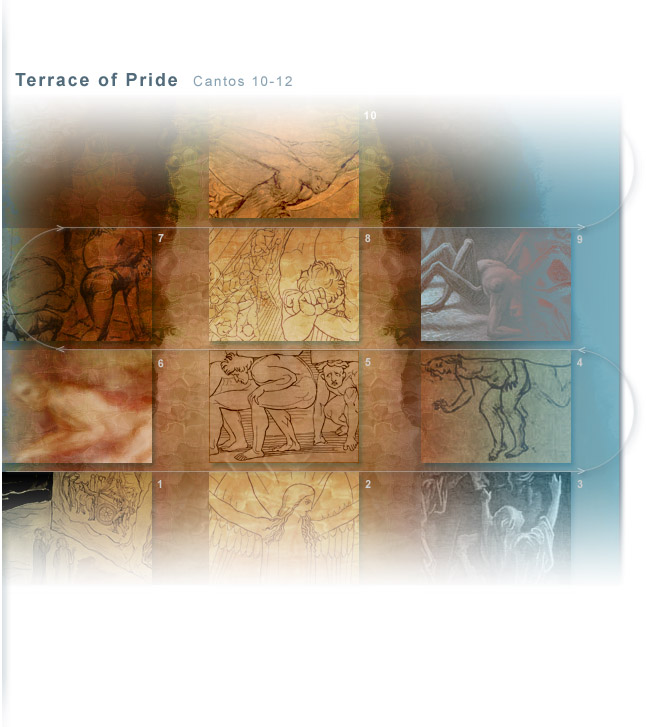

Terrace of Pride After crossing the threshold into Purgatory, Dante and Virgil climb through an opening in the rock to reach the mountain's first terrace. Here souls are cleansed of their pride, the first of the seven deadly sins. Sculpted into the white marble wall are scenes of humility (pride's opposing virtue), beginning--as do all representations of corrective virtues on the terraces--with an episode from the life of the Virgin Mary (here the "annunciation," in which she is told of her extraordinary fate), and continuing with examples from the Hebrew Bible (King David dancing before the sacred ark) and the classical world (Emperor Trajan administering to a poor widow's needs). So wondrous is the divine artistry of the sculpted images that the conversations and smells seem real to the observer. Dante and Virgil then see the proud penitents. Bent under the weight of large stones on their backs, the shades slowly circle the terrace while chanting a paraphrase of the Lord's Prayer ("Our Father who art in heaven"). Omberto Aldobrandeschi suffers here for the arrogance he shares with other members of his renowned Tuscan family, and Oderisi da Gubbio (an acclaimed illuminator of manuscripts, who now acknowledges the superior work of a rival artist) lectures Dante on the ephemeral nature of worldly glory. Following the stooped spirits around to the right, Dante and Virgil view (as do the penitents) famous examples of punished pride--beginning with Lucifer's fall from heaven and ending with the fall of Troy--sculpted on the floor of the terrace. A beautiful white angel directs the travelers to the rugged stairway rising up to the next level. As he leaves the terrace of pride, Dante hears voices singing "blessed are the poor in spirit," the First Beatitude of Jesus's Sermon on the Mount. Unsure why he feels so much lighter than he had before, Dante learns from Virgil that the angel, as he brushed Dante's brow with a wing, removed one of the seven P's carved into his forehead at the gate to Purgatory. Back to top. Proud Penitents. Cantos 10.100-39, 11.1-142 Dante singles out three individuals among the proud penitents carrying heavy rocks on their backs. The weight forces them to walk slowly, their bodies bent low to the ground. Dante compares the suffering, hunched souls to the human figures (with knees to their chest and pained expressions) used in architecture to support a ceiling or roof (10.130-5). Omberto Aldobrandeschi laments the arrogance that was common in his family, powerful ghibellines who controlled territory in the coastal region of Tuscany (11.58-69). The Aldobrandeschi boasted, according to early commentators, that their holdings were so vast they could spend each day of the year in a different castle. Omberto's pride caught up with him in 1259 when he took on a large contingent of Sienese troops. The second penitent, Oderisi da Gubbio, was a talented miniaturist and illuminator, an artist who painted colorful images in the margins of manuscripts. Born around 1240 in Gubbio (in the central Italian region of Umbria), Oderisi worked for a time in Bologna and was brought to Rome in 1295 by Pope Boniface VIII to illuminate manuscripts in the papal library. Franco Bolognese (11.82-4), according to Vasari, also worked in the library at this time and was a better artist than Oderisi, who died in Rome in 1299. Oderisi points out to Dante a third figure, Provenzan Salvani (11.109-42), a prominent ghibelline general from Siena who helped lead his forces to victory over the Florentine guelphs at Montaperti in 1260. Following this battle, Provenzan's desire (and that of other ghibelline leaders) to see Florence completely destroyed was magnanimously opposed by Farinata degli Uberti. Some years later, Provenzan was taken prisoner and killed by the Florentines, who raised his severed head high in the air in fulfillment of the misleading prophecy that this head would be held highest on the battlefield. Here in Purgatory the proud man has avoided a life-sentence in Ante-Purgatory for late repentance by virtue of a single act of humility: he literally begged his fellow citizens for ransom money to win the life of an imprisoned friend; Dante, Oderisi prophesies, will soon come to understand such humiliation first hand (11.127-42). Back to top. Whips and Bridles. As part of the purgatorial process, the spirits on each terrace, beginning here with pride, encounter examples of the virtue contrary to the vice for which they now suffer followed by examples of the vice itself. On the next terrace (13.37-42; 14.143-4), Virgil describes the role of these instructive examples in equestrian terms: the virtuous examples are "whips" meant to guide the penitent to moral righteousness, while the examples of the vice are the "bridle" (or "bit") used to curb the spirit's sinful tendencies. The pairing of each vice with its contrary virtue was common in medieval theological treatises (e.g., Hugh of St. Victor's De quinque septinis seu septenariis), and the examples Dante chooses from the life of Mary as the first representation of virtue on each terrace were well known from the popular Speculum Beatae Mariae Virginis ("Mirror of the Blessed Virgin Mary"). Back to top. Examples of Humility and Pride. Cantos 10.28-96, 12.13-69 Carved into the side of the mountain on the first terrace are exemplary images of humility. So real to life are the sculpted scenes that Dante wonders if he doesn't actually hear the words and smell the odors suggested in what he sees (10.40, 59-63). The first scene depicted (10.34-45) is drawn from the Gospels (Luke 1:26-38). The angel Gabriel (sent by God to Nazareth) announces to Mary, a young woman engaged to Joseph, that she will give birth to a son, to be named Jesus, who "shall be great and shall be called the Son of the Most High" (Luke 1:32). When Mary asks how she, a virgin, will conceive, Gabriel explains: the "Holy Ghost shall come upon thee" (Luke 1:35). Declaring herself the "handmaid of the Lord" (10.44; Luke 1:38), Mary humbly accepts her role. This "annunciation" scene is a favorite subject of medieval and early modern art, as seen in works by, among many others, Duccio di Buoninsegna, Giotto, Simone Martini, Fra Angelico, Leonardo da Vinci, and Botticelli. The next scene of humility, drawn from the Hebrew Bible (2 Kings 6:1-23), portrays David, king of Israel and "humble psalmist," dancing uninhibitedly before the ark of God as it is brought into Jerusalem (10.55-69). Michol accuses David of sullying his regal status by celebrating uncovered before even the "handmaids of his servants," to which David responds: "And I will be little in my own eyes: and with the handmaids of whom thou speakest, I shall appear more glorious" (2 Kings 6:20-22). The third and final example of great humility honors the Roman emperor Trajan (10.73-93), who fulfilled the duties of justice and mercy by delaying a military campaign to avenge the murder of a poor widow's son. Rather than delegating the woman's request to a subordinate or successor, Trajan decided that the responsibility of his high office compelled him to attend personally to this seemingly low-level matter. Notorious examples of pride, serving to rein in the sinful disposition of the shades, are carved into the floor of the terrace (12.13-69), similar in appearance to figures sculpted in the stone covers of tombs rising slightly above the ground. Beginning with Lucifer and the giant Briareus, the terrace artwork combines biblical and classical figures, including (from the Bible) Nimrod, Saul, Rehoboam, Sennacherib, and Holofernes; and (from classical sources) other giants, Niobe, Arachne, Eriphyle, and Cyrus of Persia. The entire series concludes with an image of Troy, the ancient city which Dante, echoing Virgil (Aen. 3.2-3), elsewhere calls "proud Ilium" (Inf. 1.75). Back to top. "VOM" Acrostic. Canto 12.25-63 Consistent with the artistic displays and themes on the terrace of pride, Dante calls attention to his own talent by imbedding a meaningful acrostic within his poetry: the initial letters of the verses describing infamous examples of pride (12.25-63) spell the word VOM (or "uom" since u and v are interchangeable), Italian for "MAN." That Dante views pride as nearly inseparable from the human condition accords with pride's foundational status in the Bible and medieval Christian thought. Virtually synonymous with transgression at points of origin or primacy--rebellion of the most beautiful angel (Lucifer), disobedience of the first human beings (Adam and Eve), overreaching of the mighty Nimrod (Tower of Babel)--the biblical history of pride more than warrants its identification in Ecclesiasticus as "the beginning of all sin" (10:15). This dubious distinction is repeated and reinforced throughout the Middle Ages. For Gregory the Great, pride is the "queen of vices" (Moralia in Job 31.45), while Thomas Aquinas declares that "the mark of human sin is that it flows from pride" (Summa Theologiae 3a.1.5); he variously discusses pride in relation to other sins as the "gravest," the "first," and the most "sovereign" (2a2ae.162.6-8). These and other examples show how designations of pride as both the first sin and the most dominant sin often amount to one and the same thing. Back to top. Cimabue Guido Guinizzelli The Renaissance writer Vasari claims that Oderisi was a good friend of Giotto, the most renowned artist of the so-called Proto-Renaissance. A Florentine contemporary of Dante, who most likely knew the poet, Giotto di Bondone (c. 1267-1337) was a painter, sculptor, and architect whose earlier work, including frescoes of the life of St. Francis (in Assisi, c. 1290-6) and a fresco of the Last Judgment in the Arena Chapel at Padua (1305), is thought to have influenced Dante. Breaking with the iconographic conventions of Byzantine painting, Giotto created scenes with a heightened sense of naturalness and physical reality (through the illusion of weight and three-dimensional space). He thus distinguished himself even from his master, Cimabue, as Dante now has Oderisi affirm on the first terrace of Purgatory (11.94-6). Cimabue (c. 1240-1308) was a Florentine painter whose art already challenged Byzantine conventions through an increased emphasis on representing emotion and the plasticity of figures. When, in the field of literature, Oderisi says that one "Guido" has supplanted another (11.97-9), he alludes to the poets Guido Cavalcanti and Guido Guinizzelli. Cavalcanti, whose father Dante met in Hell, was a fellow Florentine and Dante's best friend, while Guinizzelli (c. 1225-76) was considered the master of a new kind of writing--in which love and moral- intellectual excellence reinforce one another--that influenced both Cavalcanti and Dante. His canzone "Al cor gentil rempaira sempre amore" ("In the noble heart love always finds its refuge"), became a poetic manifesto of this new style. Back to top. Audio "piangendo parea dicer: 'piú non posso'" (10.139) in tears they seemed to say: "I can't bear it" Back to top. Study Questions 1. What might be Dante's reason(s) for having the proud souls stooped under the crushing weight of boulders as they walk around the first terrace of the mountain? 2. As Dante leaves the first terrace (pride), an angel erases one of the seven P's from his forehead (12.97-9). What might it mean that the remaining six P's (the initial for peccatum [sin] or poena [punishment]) all grow fainter once the first P, associated with pride, has been removed (12.115-26)? 3. Where is the line between (sinful) pride and (healthy) ambition: for Dante? For you? Back to top. Back to Purgatory main page | |

|