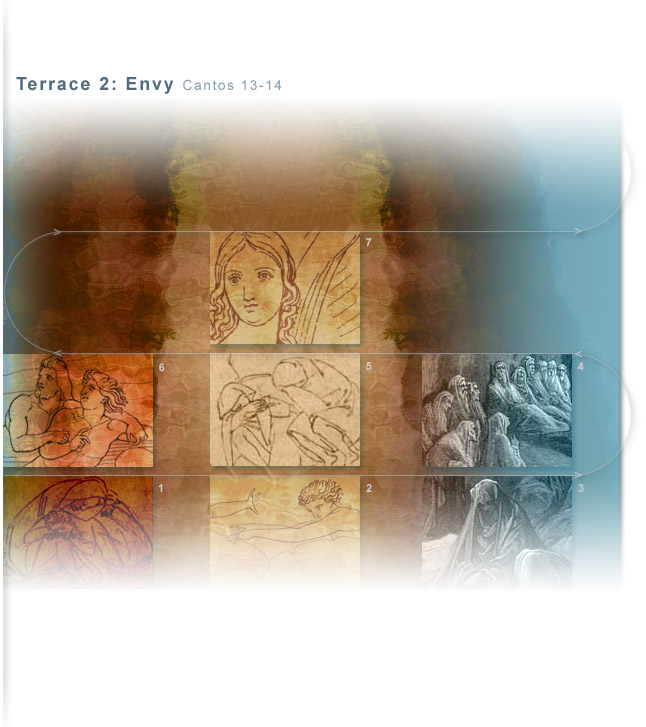

| Terrace of Envy

Encounters: Sapia. Canto 13.100-54 Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli. Canto 14.1-126 Allusions: Examples of Love and Envy. Cantos 13.28-36, 14.130-9 Dante's Pride. Cantos 13.133-8, 14.21 Gallery Audio Study Questions Home |

|

Terrace of Envy

As Dante and Virgil circle the second terrace, on which souls purge themselves of envy, disembodied voices fly past them, repeating examples of selfless love (envy's opposing virtue): Mary's concern for wedding guests, the steadfast friendship of Orestes and Pylades, and Jesus's call for people to love those who harm them. The envious penitents, clad in coarsely woven cloaks similar in color to the livid stone terrace, sit together (supported by the terrace wall and by one another) and chant the Litany of All Saints. Their eyes, to Dante's horror, are sewn shut with wire (as was done to train hawks) such that they resemble a group of blind beggars. Not to appear rude, Dante asks a question (whether there are any Italians in the group) to announce his presence. Sapia, raising her chin in Dante's direction, tells how envy caused her to seek happiness in the misfortune of others (including the defeat of her Sienese countrymen in battle); because she delayed repentance until the end of her life, she would still be among the late repentant in Ante-Purgatory, if not for the prayers of Pier Pettinaio, a saintly combseller from Siena. Two spirits from Romagna, Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli, overhear this conversation and ask Dante who he is and where he comes from. When Dante associates his birthplace with the Arno flowing through Tuscany, Guido denounces the bestial inhabitants of the cities along this river, not least Rinieri's grandson, Fulcieri, whose prophesied brutality will take a heavy toll on Florence soon after Dante's exile. Before sending Dante on his way, Guido also laments the current state of affairs in Romagna. Having left behind the sorrowful spirits, the travelers hear voices of two exemplary embodiments of envy, Cain and Aglauros. With only a few hours remaining before sundown, Dante and Virgil reach the next angel, who directs them to the stairway and removes the second P from Dante's brow. While climbing, they hear "blessed are the merciful" (the Fifth Beatitude) sung below on the terrace they have just visited. Back to top. Sapia. Canto 13.100-54 Sapia is one of the souls purging themselves of envy on the second terrace. The envious shades are seated together, leaning against one another and against boulders. Their coarsely woven cloaks are similar in color to the plain appearance of the rocks. Since they derived pleasure from seeing other people brought low, the envious are now deprived of sight in an atrocious manner: their eyes are sewn shut with iron wire. With tears squeezed out of their closed eyes, these souls huddle together like blind beggars (13.43-72). Sapia, born around 1210 into the prominent Salvani family of Siena, perversely rejoiced upon witnessing the defeat of her fellow citizens (ghibellines from Siena) at Colle di Val d'Elsa, where her proud nephew Provenzan Salvani was killed. She now puns on her name in recognition of her foolishness (despite her name--Sapia--she was not wise [savia], 13.109-10). Sapia shows her eagerness to speak with Dante by raising her chin in the direction of his voice. Back to top. Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli. Canto 14.1-126 Dante's living presence in Purgatory draws the attention of Guido del Duca and Rinieri da Calboli on the terrace of envy, though the precise relationship between these two men and the sin of envy is never made clear. Guido, born to a noble family from Ravenna, was affiliated with ghibelline politics in the early thirteenth century, and he served for a time as a judge. Rinieri belonged to a prominent guelph family (Paolucci) from Forlì, in Romagna. He was elected to important positions (podestà or chief magistrate) in several cities in the region over a long period of time. Expelled from Forlì in 1294, Rinieri died in battle soon after returning in 1296. Guido presents his honorable companion to Dante as an example of a good family gone bad, an all too common occurrence in Romagna, a region in north-central Italy (14.91-126). But Guido doesn't spare Tuscany, Dante's home region, from his critique: on the contrary, he says that the river (Arno) is best left unnamed because it passes through cities characterized as unsavory beasts, from "foul hogs" (Casentino) and "curs" (Arezzo) to "wolves" (Florence) and deceiving "foxes" (Pisa) (14.43-54). Seeing future events with a bearing on Dante's life, Guido breaks the bad news that Rinieri's grandson, Fulcieri da Calboli, will dishonor his family name by spilling blood as the "hunter" of Florentine "wolves" (14.58-66). Indeed, Fulcieri viciously persecuted white guelphs (Dante's party) and ghibellines after he was elected podestà of Florence by the ruling black guelphs in 1302-3. He later augmented his reputation for cruelty while serving as podestà of other cities before his death in 1340. Back to top. Examples of Love and Envy. Cantos 13.28-36, 14.130-9 Disembodied voices shout the examples of love and envy on the second terrace. In the first of three manifestations of loving concern for others, Mary informs her son Jesus, present with his disciples at a wedding celebration in Cana, that there is no wine for the guests, vinum non habent ("they have no wine") (13.28-30). Performing his first miracle, Jesus then changes into wine the water contained in six large pots (John 2:1-11). The second echoing voice, "I am Orestes" (13.31-3), alludes to a double act of love from the classical tradition: condemned to death for the murder of his mother Clytemnestra (who had killed his father, Agamemnon), Orestes insists on revealing his true identity (and accepting the consequences) after Pylades tried to spare Orestes' life by dying in his place; each friend proclaimed "I am Orestes" to save the life of the other (Cicero, On Friendship 7.24). "Love those who have done harm to you," the third example of love (13.34-6), encapsulates one of Jesus' lessons to his disciples in the Sermon on the Mount: "Love your enemies: do good to them that hate you: and pray for them that persecute and calumniate you" (Matt. 5:44). The first of two spoken allusions to envy, "whoever captures me will kill me" (14.133), repeats the lament of Cain to God (Genesis 4:14) after God has cast him out as a "fugitive and vagabond" for having killed his brother Abel out of envy. God replies that anyone who kills Cain will be "punished sevenfold," and he places a mark on Cain to protect him (Genesis 4:15). "Caina," derived from Cain's name, designates the area of the ninth circle of Hell in which traitors to family are punished. The second voice, crying "I am Aglauros who became stone" (14.138), belongs to one of the daughters of Cecrops, an Athenian ruler. Aglauros, according to Ovid's account, crosses Minerva when she disobeys the goddess and opens a chest concealing a baby (Met. 2.552-61). After Mercury falls in love with Aglauros' beautiful sister Herse, Minerva exacts revenge by calling on Envy to make Aglauros sick with jealousy over her sister's good fortune. When Mercury comes to visit Herse, Aglauros attempts to bar the entrance to the god, who promptly transforms her into a mute, lifeless statue (Met. 2.708-832). Back to top. Dante's Pride. Cantos 13.133-8, 14.21 On the terrace of envy, Dante admits that he already feels the weight of rocks used to flatten the pride of penitents on the first terrace (13.138) (audio), and he perhaps confirms the likely realization of this fear when he remarks that his name is not yet well known (14.21) (audio). Such frank self-awareness encourages us to consider possible illustrations of Dante's pride thus far in the poem / journey: his self-inclusion among the great poets in Limbo, "so that I was sixth among such intellect" (4.102) (audio); his claim to superiority over the classical authors Lucan and Ovid in the presentation of the thieves; and his close identification with the Greek hero Ulysses. Back to top. Audio "che già lo 'ncarco di là giù mi pesa" (13.138) already the load down there weighs on me "ché 'l nome mio ancor molto non suona" (14.21) since my name is not yet well known Back to top. Study Questions 1. Explain the relationship between eyesight and the vice of envy. Why do the envious souls on the second terrace have their eyes sewn shut? 2. What is the significance of Dante's awareness of his own pride as he speaks with Sapia on the terrace of envy (13.133-8)? Back to top. Back to Purgatory main page | |

|