| Terrace of Wrath

Encounters: Marco Lombardo. Canto 16.46-129 Allusions: Examples of Gentleness and Wrath. Cantos 15.85-117, 17.19-39 Two Suns Theory. Canto 16.106-32 Free Will. Cantos 16.67-102, 18.61-75 Gallery Audio Study Questions Home |

|

Terrace of Wrath

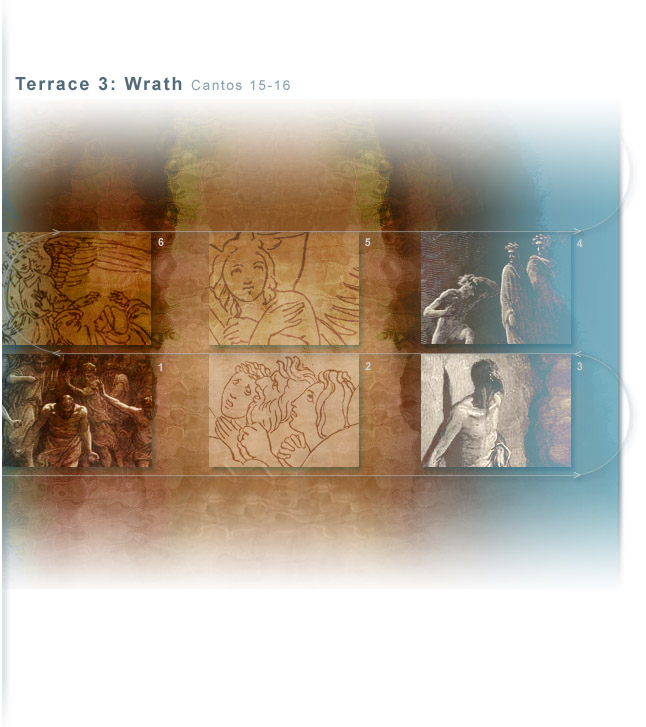

After Virgil explains to Dante how spiritual love (unlike love of earthly goods) only increases for each individual as more and more people partake of it, the travelers arrive on the third terrace in Purgatory, where souls cleanse themselves of wrath. Here, as Dante learns firsthand, the penitents receive didactic examples of anger and its contrary virtue (meekness or restraint) in the form of hallucinatory visions. Dante first envisions three virtuous acts: Mary's measured response to young Jesus's three-day absence; the refusal of Pisistratus, ruler of Athens, to avenge the amorous advances of his daughter's suitor; and Saint Stephen's dying prayer for the forgiveness of his attackers. As day comes to an end, the remaining sunlight is cut off by dense smoke, pitch-black and filthy, that forces Dante to shut his eyes. Keeping a hand on Virgil's shoulder, he hears the penitents praying the Agnus Dei ("Lamb of God"), seeking peace and mercy. Dante carries on a conversation with one spirit, their speech serving to keep them close together as they circle the darkened terrace. Marco Lombardo, a chivalrous man of the world, informs Dante that humankind (not celestial influence) is at fault for the absence of virtue (and abundance of malice) in the world because individuals possess the gift of free will. However, Marco places the greatest blame on leaders, political and religious, whose misrule harms individuals and society, and particularly the current pope (Boniface VIII), who sullies the church by claiming both spiritual and temporal authority. Marco turns back as Dante and Virgil emerge from the cloud of black smoke. Walking once again in the fading daylight, Dante witnesses (in his mind) wrath manifested as familial violence (Procne), genocidal rage (Haman), and spiteful harm to oneself (Amata) and thus to loved ones. An angel, whose brilliance overwhelms Dante's vision, directs the travelers to the next stairway; as Dante begins to climb, he feels the angel's wing touch his face (to remove the third P) and hears a version of the Seventh Beatitude, beginning "blessed are the peacemakers." Back to top. Marco Lombardo. Canto 16.46-129 The souls purging themselves of their wrathful dispositions are forced to walk through thick acrid smoke that is darker than night (15.142-5; 16.1-15). Unable to see the outside world with their eyes, the penitents experience hallucinatory visions in which they first "see" examples of meekness (the virtue opposite to wrath) and then "see" examples of wrath itself. Marco, who comes from the region of Lombardy in northern Italy (or perhaps belonged to the Lombardi family of Venice), is a courteous, eloquent, and well informed interlocutor. He says little about himself but instead serves as a mouthpiece for some of Dante's most cherished ideas about the relationship between celestial influences and human responsibility, and the balance of power between religious and political institutions. Early commentators and chroniclers tell various stories about Marco: he gave generously of his considerable wealth to those in need, and he forgave all debts upon his death (Buti); he was resolved to die in prison rather than regain his freedom through the financial contributions of his many Lombard colleagues, thus shaming a local ruler into paying the entire ransom himself (Benvenuto); invited to a lavish birthday party for Count Ugolino della Gherardesca, Marco observed that his host was primed for a harsh reversal of fortune (Villani). All attest to Marco's exemplary courtly virtues. Back to top. Examples of Gentleness and Wrath. Cantos 15.85-117, 17.19-39 The instructive cases of the virtue contrary to wrath (gentleness, forbearance) and the vice itself are experienced by the spirits--and now by Dante--as "ecstatic visions" (15.85-6), "non false errors" (15.117) insofar as they convey truth even though they occur only in the mind of the person seeing them. In the first example of gentleness (15.85-93), Mary displays remarkable restraint upon finding Jesus, her twelve-year old son, in the temple of Jerusalem conversing with learned adults. Jesus had come to Jerusalem with his parents for the Passover celebration, but he stayed behind when Mary and Joseph returned home (unbeknownst to them) and it took them three days to find him (Luke 2:41-8). In response to Mary's gentle rebuke, cited verbatim by Dante ("Why have you done this to us?"), the young Jesus asks, "How is it that you sought me? Did you not know that I must be about my father's business?" (Luke 2:49). Dante's second case of gentleness (15.94-105), from the classical tradition, is recounted by Valerius Maximus (Factorum et dictorum memorabilium 5.1.2): Pisistratus, a tyrannical ruler of ancient Athens (560-527 B.C.E.), counters his wife's wish for vengeance with a calm, accepting attitude toward the young man who, in love, had kissed their daughter in public. If they kill those who love them, Pisistratus asks, what should they do to their enemies? Stephen, whose martyrdom is recounted in the Bible (Acts 6-7), causes a stir with his preaching in the name of Jesus and is brought before the council to defend himself against charges of blasphemy. He concludes a long speech by accusing the council members of betraying and murdering the "Just One," much as, he claims, their fathers persecuted the prophets (Acts 7:52). Enraged, they cast Stephen out of the city and stone him to death; as he dies, Stephen asks the Lord to "lay not this sin to their charge" (Acts 7:57-9), the scene Dante now includes as the final instance of exemplary gentleness (15.106-14). Procne, Dante's first example of wrath (17.19-21), kills her small son Itys and feeds his cooked flesh to her husband Tereus, King of Thrace, upon learning that he raped Philomela (Procne's sister) and cut out her tongue to prevent her from telling what had happened. Philomela ingeniously managed to inform Procne of the crime by weaving a tapestry that told the story in pictures. Dante here singles out the cruel vengeance wrought by Procne (with help from her sister). Made aware that he has eaten his son, an enraged Tereus, his sword drawn, chases the two sisters but before he can catch them all three are transformed into birds: Tereus into a hoopoe (a crested bird with a long beak), Procne into a nightingale, and Philomela into a swallow (in some versions Philomela is the nightingale and Procne the swallow). The gruesome story is told by Ovid (Met. 6.424-674). Dante chooses as his second example of wrath (17.25-30) the biblical figure Haman, whose cruelty is recounted in the Book of Esther. The most favored prince of King Assuerus, ruler of an empire stretching from Ethiopia to India, Haman takes offense at Mordecai, a Jew who refuses to bow down to him. Haman's anger is such that he calls for the killing of not only Mordecai but all Jews throughout the kingdom, "both young and old, little children and women, in one day . . . and to make a spoil of their goods" (Esther 3.13). Haman's genocidal plan turns against him when Mordecai, called "just" by Dante (17.29), convinces Queen Esther to intervene. Esther, herself a Jew who is also the niece and adopted daughter of Mordecai, reveals Haman's plot to King Assuerus (he was previously unaware of his wife's background); Assuerus promptly has Haman hanged on the same gallows he (Haman) had prepared for Mordecai. (Haman is "crucified" instead of "hanged" in Purgatorio 17.26 because the gallows are described as a cross, "crux," in the Vulgate, the Latin Bible familiar to Dante [Esther 5:14; 8:7].) The king also reverses Haman's orders, so that the Jews in his realm are spared and their persecutors killed instead, and he elevates Mordecai (already honored for having foiled a plot to assassinate Assuerus) to a position of power. Queen Amata, whose story is told in Virgil's Aeneid (7.45-106, 249-73, 341-405; 12.1-80, 593-611), inspires the third and final vision of wrath on the third terrace of Purgatory (17.34-9). Wife of King Latinus, Amata sought the marriage of her daughter Lavinia to Turnus (ruler of the Rutulians, Italian allies), but Latinus accepted the oracle's demand that she marry a foreigner, namely, the Trojan hero Aeneas. While, due to machinations of the gods, resolution of this matter is delayed and war rages, Amata mistakenly believes Turnus has been killed in battle (Aeneas will kill him at a later point). Acting on her furious despair, the queen takes her own life, thus depriving Lavinia of her mother. Back to top. Two Suns Theory. Canto 16.106-32 Marco Lombardo articulates Dante's view of the Empire and Papacy as separate, autonomous institutions. Rome used to possess "two suns," he says, one showing the world's path and the other God's path; but over time these two lights have extinguished one another, and, switching metaphors, the sword and the shepherd's staff are now joined, much to the detriment of humanity (16.106-11). Dante's model of "two suns," each deriving its authority directly from God, challenges the medieval Christian notion of the pope as "sun" and the emperor as "moon" (based on Genesis 1:16), with the lesser sphere wholly dependent on the greater sphere for its authority and influence. Dante later writes a treatise dealing specifically with this issue of spiritual and political power: he argues in Monarchia that even the sun-moon analogy fails to prove papal dominion over temporal matters because the two spheres possess their own powers, including (Dante believed) their own light (3.16). Although he concedes that the emperor must show reverence to the pope, like a son to a father, Dante believes strongly in their independence as divinely sanctioned guides for humanity: "one is the Supreme Pontiff, to lead humankind to eternal life, according to the things revealed to us; and the other is the Emperor, to guide humankind to happiness in this world, in accordance with the teaching of philosophy" (Monarchia 3.16). A measure of the daring (and risk) in Dante's political philosophy is readily seen from a comparison of his ideas with sentiments expressed by Pope Boniface VIII in a papal bull of 1302 ("Unam Sanctam"). Adopting the common metaphor of "two swords," one each for spiritual and temporal authority, Boniface declares that they both "are in the power of the Church" and "one sword ought to be under the other and the temporal authority subject to the spiritual power." He continues by proclaiming a sort of papal infallibility, a highly ironic notion in light of Dante's treatment of the papacy, particularly under Boniface, in the Divine Comedy: "Therefore, if the earthly power errs, it shall be judged by the spiritual power, if a lesser spiritual power errs it shall be judged by its superior, but if the supreme spiritual power errs it can be judged only by God not by man." Later Church leaders evidently felt much as Boniface did, for they condemned Dante's contrary ideas as heretical and repeatedly censored his Monarchia: in 1329 a prominent cardinal ordered all copies of the work to be burned, and in the sixteenth century the book was included in the Church's Index of banned books. It wasn't until 1881 that Dante's book was removed from the list. Dante views Marco's condemnation of the Church's claim to both worldly and spiritual authority as a modern confirmation of the biblical injunction to Levi's sons (16.130-2): God instructs Aaron that he and his descendents (of the tribe of Levi), chosen to perform priestly functions in the tabernacle, have rights to only what is required for "for their uses and necessities" and "shall not possess any other thing" (Numbers 18:20-4). Back to top. Free Will. Cantos 16.67-102, 18.61-75 Dante's placement of a discussion of free will at the center of the Purgatorio, and therefore at the center of the entire Divine Comedy, accords with the importance of this notion not only for medieval theological debate but for Dante's fundamental premise of the poem: as stated in the Letter to Can Grande, an individual becomes "liable to the rewards or punishments of justice" through the exercise of free will. Marco Lombardo explains that while the heavens exert influence over human desires, individuals (because they have free will) are responsible for their actions (16.67-78). He focuses on the socio-political implications of human responsibility insofar as guidance--in the form of laws and leadership--is required to direct individual souls to proper ends. Marco concludes that misrule, due primarily to the Church's illegitimate claim to temporal authority, is the reason the world has fallen into corrupt ways and virtue is so rarely seen (16.103-29). Virgil, on the next terrace, discusses free will in relation to love and the process of making judgments for which the individual is fully accountable. Human will is an "inborn freedom," a "noble power" that counsels the individual to actions subject to praise or blame (18.61-75). Free will for Dante, as for the theologian Thomas Aquinas, amounts to freedom of judgment, the choice of pursuing or avoiding what is apprehended and then judged to be good or bad according to the dictates of reason. Back to top. Audio "io riconobbi i miei non falsi errori" (15.117) I recognized my non false errors Back to top. Study Questions 1. Why must the shades of the wrathful purify themselves within an atmosphere of dark, filthy smoke? 2. How do you understand the relationship between Dante's conception of free will (individual responsibility) and his "two suns" theory, the role of religious leaders and political rulers in their respective spheres (spiritual, temporal) (see 16.73-114)? Back to top. Back to Purgatory main page | |

|