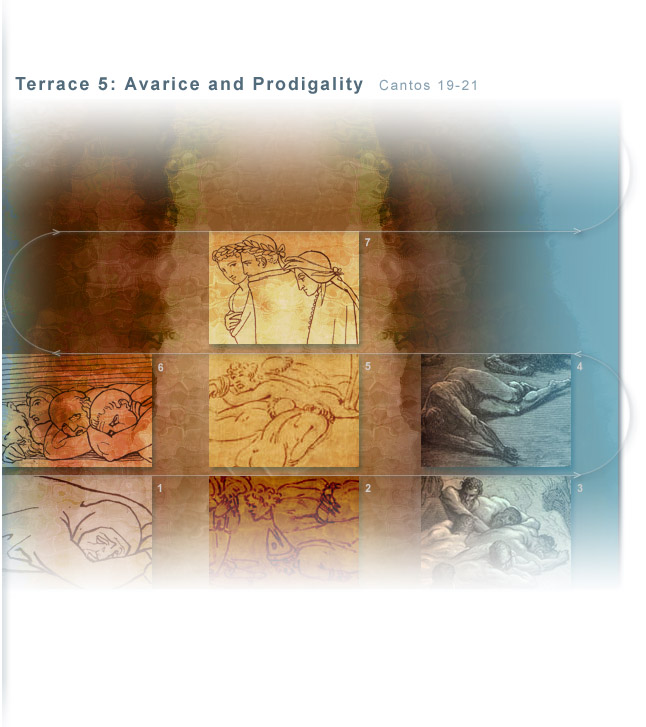

| Terrace of Avarice & Prodigality

Encounters: Pope Adrian V. Canto 19.88-145 Hugh Capet. Canto 20.43-123 Statius. Cantos 21 and 22 Allusions: Examples of Poverty and Avarice. Canto 20.19-33, 103-17 Gallery Audio Study Questions Home |

|

Terrace of Avarice & Prodigality

On the fifth terrace Dante sees shades who purify themselves of avarice (or its sinful opposite, prodigality) by lying facedown, immobile and outstretched, on the hard rock floor. Weeping and sighing, they recite a biblical verse that perfectly describes their current state (Purg. 19.73): Adhaesit pavimento anima mea ("My soul hath cleaved to the pavement"; Psalm 118:25 [Psalm 119 in the King James Bible]). One penitent, identified as Pope Adrian V , tells how he turned to God and repented of his avaricious ways only after his election to the papacy in 1276 (he died soon after). Another avaricious soul describes, in tears, instructive examples of virtuous behavior: Mary's acceptance of her indigence (made evident when she gave birth to Jesus in a manger), Fabricius's preference for honorable poverty over tainted wealth during his service to the Roman Republic, and the anonymous dowries provided by Saint Nicholas (better known as Santa Claus) to prevent a poor father from forcing his three daughters into prostitution. The voice Dante hears belongs to Hugh Capet, founder of the line of French royalty that, plagued by greed and corruption, will soon (Hugh prophesies) harm both Florence and Pope Boniface VIII. Dante learns that when night falls the penitents recite a litany of avaricious exemplars, including allusions to Midas, the Roman leader Crassus, and Sapphira, who, with her husband, tried to defraud the apostles. Continuing around the terrace, Dante and Virgil feel the mountain tremble and hear a shout of praise to God, celebratory signs that a spirit has been cleansed and is now free to move up the mountain. The purified shade is Statius, a Latin poet who found inspiration to become both a poet and a Christian in the writings of Virgil, himself consigned to Limbo. An angel, having removed the fifth P from Dante's brow and blessed those who thirst after justice (Fourth Beatitude), directs all three poets to the next terrace. Back to top. Pope Adrian V. Canto 19.88-145 The souls on the fifth terrace purify themselves of their vice (avarice or its sinful opposite, prodigality) by lying face-down on the hard rock floor. Weeping and praying, they themselves call out the examples of greed and its opposing virtue (generosity). Pope Adrian V, who lived only a little more than a month after his election to the papacy in 1276 (19.103-5), explains how this prostrate position is fitting punishment for their neglect of spiritual matters and excessive attachment to worldly goods. This pope, the first saved pope encountered by the journeying Dante, tells his visitor not to kneel because they are now equals before God (19.133-5). Back to top. Hugh Capet. Canto 20.43-123 Dante's combines two Hugh's--Hugh Capet the Great (d. 956) and his son, Hugh (ruled 987-96)--into this composite "Hugh Capet," root of the medieval French dynasty of Capetian rulers. Of humble origins himself, according to Dante's version, Hugh Capet laments the corruption of his ruling descendents as they acquired power and privilege over the centuries. He prophesies events of particular interest to Dante: the coup d'état in Florence plotted by Pope Boniface VIII and staged by the black guelphs with the help of the French prince, Charles of Valois; and the abduction and humiliation of Boniface at the hands of forces controlled by King Philip IV (Philip the Fair) of France (20.85-90). Like Pope Adrian V, Hugh Capet lies prostrate on the floor of the fifth terrace to expiate the sin of avarice. Back to top. Statius. Cantos 21 and 22 Statius, a Roman poet from the first century (45-96 C.E.), is the author of two epic Latin poems, the Thebaid (treating the fratricidal war for the city of Thebes) and the Achilleid (about the Greek hero Achilles), which was left incomplete upon the poet's death. Dante and Virgil meet Statius soon after he has completed his time on the fifth terrace, an achievement that triggers the trembling of the mountain and the celebratory shouting of the spirits (20.124-41; 21.58-72). Statius spent over five hundred years on the fifth terrace (not for avarice but for its symmetrical vice, prodigality), after having raced around the fourth terrace (sloth) for over four hundred years (22.92-3). The reverence Statius shows for Virgil reflects how much he owes to his Roman precursor: Statius drew poetic inspiration from Virgil's Aeneid (calling it a "divine flame" in 21.95), and he credits Virgil's fourth eclogue with his turn to Christianity (22.64-73); Statius also credits a line from the Aeneid with teaching him to curb his free spending ways, thus enabling him to avoid the eternal punishment of rolling boulders with the avaricious and prodigal sinners in Hell (22.37-45). Freed of his purgatorial trials, Statius will accompany Dante and Virgil the rest of the way up the mountain. Back to top. Examples of Poverty and Avarice. Canto 20.19-33, 103-17 The penitents on the fifth terrace, Hugh Capet explains, recite examples of avarice during the night and examples of the contrary virtue (poverty, contentment with little) during the day (20.97-102). Because Dante and Virgil arrive on the terrace in the morning, they first hear the exemplary cases of poverty, beginning as always with a biblical scene from the life of Mary (20.19-24). Her poverty is evident, the spirits proclaim, from the extremely modest circumstances in which she gave birth to Jesus, as described in Luke 2:7: "And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn." "Good Fabricius," a classical figure, is the second virtuous example (20.25-7). Gaius Fabricius Luscinus was a prominent Roman leader--he served the Republic twice as consul (282 and 278 B.C.E.) and once as censor (275)--legendary for his integrity and contempt for material wealth. So strong was Fabricius' loyalty to the state that he could not be bought off with lavish gifts, preferring instead "to remain in poverty as an ordinary citizen" (Augustine, City of God 5.18). Dante elsewhere presents Fabricius as a model of Roman civic virtue based on this impressive austerity (Convivio 4.5.13; Monarchia 2.5.11), which Virgil succinctly praises in the Aeneid: "Fabricius, strong with so little" (6.843-4). Nicholas, whose generosity enabled the young women to maintain honor (20.31-3), is the third individual praised on the terrace of avarice. St. Nicholas, venerated by both the Greek and Roman Churches, was the fourth-century bishop of Myra (in Asia Minor) whose remains were brought to Bari, Italy in the eleventh century (he is also known as Nicholas of Bari). The episode recited by the penitents was well known from The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints, compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in the thirteenth century. Born to a wealthy family, Nicholas resolved to distribute his riches "not to the praising of the world but to the honor and glory of God." He acted on this promise upon learning that a neighbor, an impoverished nobleman, intended to keep the family afloat by prostituting his three daughters. Nicholas, horrified by this proposition, stealthily threw a bundle of gold into the man's house during the night. Thanking God, the neighbor used the gold to marry his oldest daughter. Nicholas repeated the procedure two more times, thus providing a dowry for all three daughters. The patron saint of sailors, virgins, merchants, and thieves (among others), Nicholas is most widely recognized as Santa Claus, patron saint of children. During the night, the penitents recite, in rapid succession, seven infamous cases of avarice (20.103-17). Pygmalion, a traitor, thief, and parricide (20.103-5), was King of Tyre and brother of Dido. "Blinded by his love of gold" (Aen. 1.349), he brutally murdered Dido's wealthy husband Sychaeus (who was Pygmalion's uncle) and tried to keep the crime from his sister. Dido learned of the murder from Sychaeus' spirit, who also revealed the location of gold and silver to his sister and warned her to flee their homeland at once. Dido and her companions escaped with the treasure of rapacious Pygmalion, and they eventually founded a new city, Carthage (Aen. 1.335-68). Midas, a Phrygian king, was granted a wish by Bacchus for having returned the satyr Silenus to the god; he asked that whatever he touched be turned to gold. This was indeed an unwise choice, for now Midas could neither eat nor drink: even the solids and liquids that passed his lips turn to metal. Bacchus answered Midas' plea for forgiveness and cancelled the unwelcome gift (Ovid, Met. 11.85-145). The next three examples are biblical. Achan was stoned to death, his family and possessions consumed by fire, for having disobeyed Joshua's command that the treasures of the conquered city of Jericho be consecrated to God (Jos. 6:18-19). Because Achan took precious items from the spoils for himself, the Israelites were defeated and they suffered heavy losses in a subsequent battle; God's wrath was averted with the punishment of Achan's crime (Jos. 7:1-26). The avarice of two early Christian followers, Sapphira and her husband Ananias, was also punished by death. While other members of the community sold their property and gave all proceeds to the apostles for distribution according to need, Ananias (with the complicity of Sapphira) kept part of the sale for himself. Confronted by Peter for the fraud, first Ananias and then Sapphira immediately dropped dead (Acts 4:32-7; 5:1-10). King Seleucus of Asia sent Heliodorus to the temple in Jerusalem to bring back money, which the king, acting on false information, believed was his. The temple members, because the funds actually belonged to them and were used for charity, were distraught until their prayers were answered: as Heliodorus prepared to take away the money, there appeared a knight in golden armor whose horse delivered the kicks now praised by the penitents in Purgatory (20.113; 2 Mach. 3:25). Two classical figures round out the exemplary cases of avarice. Polymnestor lives in infamy all around the mountain (20.114-15). The king of Thrace, he was entrusted with the safety of Polydorus, youngest son of Priam and Hecuba. Driven by his insatiable greed, Polymnestor instead killed Polydorus to take for himself the considerable wealth the boy brought for safe keeping from the besieged city of Troy (Aen. 3.19-68; Met. 13.429-38). Hecuba avenges this crime: pretending to believe that Polydorus is still alive, she tells Polymnestor that she has a secret store of gold for him to give her son; when the murderer, greedier than ever, asks for the gold and promises to fulfill Hecuba's request, she grabs him and, assisted by other Trojan women, gouges out his eyes and--through the empty sockets--his brain as well (Met. 13.527-64). Marcus Licinius Crassus, part of the triumvirate with Caesar and Pompey (60 B.C.E.) and twice consul with Pompey (70, 55 B.C.E.), also suffers a gruesome death due to his avarice. Nicknamed Dives ("the wealthy one": Cicero, On Duties 2.57), Crassus comes to know the taste of gold, as the avaricious spirits mockingly put it (20.117), when greed leads to his death--and the massacre of eleven Roman legions--at the hands of the Parthians. Crassus' head and right hand are brought before the Parthian king, who has melted gold poured into the open mouth so that "as the living man burned with lust for gold, now even his dead body feels the heat of gold" (Florus, Epitoma 1.46). Back to top. Audio "e nulla pena il monte ha più amara" (19.117) there is no more brutal punishment on the mountain Back to top. Study Questions 1. Among the avaricious souls (fifth terrace), Dante has his first encounter with a saved pope, Adrian V (19.79-145). Compare the presentation of this pope with that of Pope Nicholas III among the simonists in Hell (Inferno 19). 2. Consider the important role of Virgil's writing in the life of Statius, a later Latin poet (21.94-102; 22.64-73). What effect do these passages have on your perception of Virgil? Back to top. Back to Purgatory main page | |

|