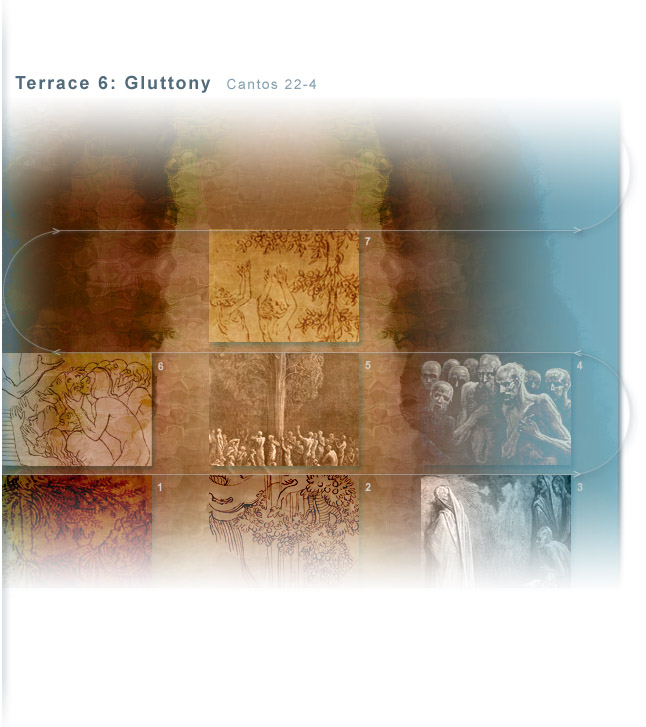

| Terrace of Gluttony

Encounters: Forese Donati. Cantos 23.37-117, 24.7-27, 70-97 Bonagiunta da Lucca. Canto 24.19-63 Allusions: Virgil's "Messianic" Eclogue. Canto 22.64-73 Examples of Temperance and Gluttony. Cantos 22.142-54, 24.121-6 Dante's Tenzone with Forese. Canto 23.115-17 "Sweet New Style" (dolce stil novo). Canto 24.49-62 Gallery Audio Study Questions Home |

|

Terrace of Gluttony

Dante and Virgil, accompanied by Statius, reach the sixth terrace, where gluttony is purged, late in the morning (it is now Easter Tuesday). There they come upon a strange tree bearing fragrant fruit; clear water falls onto its leaves from the rocks above. A voice, its source hidden among the branches, which spread wider toward the top, announces that this fruit and water will be withheld and extols models of temperance: Mary's minimal regard for her own cravings at a wedding feast, abstemious women of ancient Rome, Daniel's emphasis on wisdom over food, the pure simplicity of the mythological golden age, and John the Baptist's frugal existence in the wilderness. Turning around, Dante sees a crowd of penitents approaching swiftly. Singing,"O Lord, thou wilt open my lips: and my mouth shall declare thy praise" (Psalm 50:17 [Psalm 51:15 in the King James Bible]), the weeping shades are emaciated, their eyes sunk deep within their sockets. Dante is recognized by a friend from his youth, Forese Donati , who explains that the denial of nourishment causes the spirits' "bodies" to waste away. Having died less than five years earlier, Forese attributes his speedy progress up the mountain to the prayers of his wife (Nella). He proclaims the blessedness of his sister, already in Heaven, and the future demise and damnation of his wicked brother, an enemy of Dante. Forese points out other penitents in his group, including the poet Bonagiunta da Lucca, who cites the opening verse to one of Dante's lyrics and praises the "sweet new style" that elevates Dante above other Italian poets of the time. Further along, Dante sees another tree laden with forbidden fruit. A voice within the branches associates this tree with the one from which Eve ate and recalls two instances of gluttonous behavior, one from classical mythology (Centaurs) and one from the Bible (Gideon's men). An angel, glowing bright red, directs Dante, Virgil, and Statius to the next passageway and removes the sixth P from Dante's brow before altering the Fourth Beatitude to bless those who (illumined by grace) moderate their hunger. Back to top. Forese Donati. Cantos 23.37-117, 24.7-27, 70-97 Forese was a childhood friend of Dante in Florence and a relative of Dante's wife (Gemma Donati). He died in 1296. In their youth Forese and Dante exchanged a series of sonnets (a literary genre known as tenzone), in which they honed their poetic craft by playfully and cleverly insulting one another in the basest terms. Dante, for instance, not so subtly hints at Forese's dissolute ways and his inability to "satisfy" his wife, while Forese implicates Dante's father (and Dante himself) in shady financial dealings. Dante now encounters Forese on the terrace of gluttony, where the emaciated spirits (their eyes sunk so far back into their sockets the face resembles the letter M) suffer excruciating hunger and thirst. In the purgatorial spirit of repentance, Forese (along with Dante) looks back on his wild past with sorrow, and he credits the prayers of his good wife Nella for enabling him to advance so far up the mountain in a relatively short time (less than 5 years since his death). Back to top. Bonagiunta da Lucca. Canto 24.19-63 Another poet on the terrace of gluttony (thus drawing our attention to the mouth as a conveyor of both words and food), Bonagiunta came from the Tuscan city of Lucca (born c. 1220). He played an important role in the development of Italian lyric poetry, which drew its inspiration from the Provençal poetry of the Troubadours and first flourished in Sicily (at the court of Frederick II) before taking hold on the Italian peninsula. Not held in particularly high regard by Dante as a poet, Bonagiunta mumbles a word--"Gentucca"-- generally thought to be the name of the woman he prophesies will aid Dante in exile. Bonagiunta also heaps praise on Dante, first by citing the opening to one of Dante's most famous lyric poems (the canzone, included in the Vita Nuova, "Ladies who have understanding of love"), and then by distinguishing Dante's poetry (and perhaps that of a few others) from the poetry of earlier literary leaders and their followers: the "Notary" is Giacomo da Lentini, leader of the Sicilian school of poetry (and presumed inventor of the sonnet form), and "Guittone" is Guittone da Arezzo, a prolific Tuscan writer (he died in Florence in 1294) whose highly stylized, artificial poems were found lacking by Dante. Back to top. Virgil's "Messianic" Eclogue. Canto 22.64-73 By having Statius credit Virgil's fourth eclogue with his turn to Christianity (22.67-73), Dante follows the medieval tradition of creatively interpreting the Latin poem (written c. 42-39 B.C.E.) as a prophecy of the birth of Jesus. While Virgil likely placed his prophetic hopes on the future child of one of Rome's leading couples (perhaps Antony and Octavia), the poem's theme of messianic renewal, combined with references to a virgin and child, well served the purposes of those, like Dante, who wished to view the great Roman poet as a prophet of Christianity. Now the last age of Cumae's prophecy has come; The great succession of centuries is born afresh. Now too returns the Virgin, Saturn's rule returns; A new begetting now descends from heaven's height. O chaste Lucina, look with blessing on the boy Whose birth will end the iron race at last and raise A golden through the world: now your Apollo rules. And, Pollio, this glory enters time with you; Your consulship begins the march of the great months; With you to guide, if traces of our sin remain, They, nullified, will free the lands from lasting fear. He will receive the life divine, and see the gods Mingling with heroes, and himself be seen of them, And rule a world made peaceful by his father's virtues. (Eclogue 4.4-17) (The Eclogues, trans. Guy Lee [Harmondsworth and New York: Penguin, 1984], 57) The appearance of the "messianic" eclogue at this point in the poem is part of a larger cluster of Christ-centered references in and around the presentation of Statius on the fifth terrace. These include biblical allusions to the birth of Jesus (20.136-41; Luke 2:8-14), his encounter with the Samaritan woman (21.1-4; John 4:4-29), the passion and crucifixion (20.73-4, 85-93; Matt. 26:46-9, 27:22-38), and the resurrection (21.7-13; Luke 24:13-36). Not coincidentally, the name Christ (Cristo) appears for the very first time in the Divine Comedy in this episode (20.87). Back to top. Examples of Temperance and Gluttony. Cantos 22.142-54, 24.121-6 Two remarkable trees rise up from different locations on the sixth terrace to excite desire in the spirits for food and drink only to frustrate this craving, for the souls here expiate the sin of gluttony. From the branches and leaves of each tree resounds an anonymous voice summarizing famous examples of temperance, in one case, and exemplary instances of gluttony, in the other. Dante once again refers to the biblical scene of the wedding feast at Cana (John 2:1-5), in which Mary tells her son Jesus "they have no wine" (see "Examples of Love"), this time to underscore Mary's concern not for herself but for the welfare of the guests (22.142-4). The second example, praising the Roman women for being satisfied with water (22.145-6), is likely based on the claim of Thomas Aquinas, quoting Valerius Maximus, that "among the ancient Romans women drank no wine" (Summa Theologiae 2a2ae.149.4). Valerius says such abstemious behavior kept them from inadvertently doing something shameful (Factorum et dictorum memorabilium 2.1.5). Daniel, who was granted understanding of visions and dreams as well as "knowledge and understanding in every book and wisdom" (Daniel 1:17), serves as the next example of virtuous self-control (22.146-7). Taken from Jerusalem to Babylon, Daniel grows stronger and wiser when he abstains from the king's meat and wine (Daniel 1:8-20). Also admired for their temperance are those who lived in the Golden Age (22.148-50)--a mythical time of social harmony, pristine beauty, and an abundant supply of nature's gifts--when the human race was "content with foods that grew without cultivation" (Ovid, Met. 1.89-112). Dante's source for his final virtuous figure returns full circle to the Gospels (22.151-4): preaching in the desert of Judea, John the Baptist wore a garment of camel's hair and subsisted on locusts and wild honey (Matt. 3:1-4). Within the branches of the second tree emerges a mysterious voice that first identifies the tree as an offshoot of yet another tree, located higher up, whose fruit was eaten by Eve (24.116-17) and then recalls two noteworthy episodes of gluttony or self-indulgence (24.121-6). The cursed creatures (born of the clouds) with double chests are the Centaurs, horse-men well known for their bouts of debauchery. One such episode occurred at a wedding celebration when Eurytus, the fiercest Centaur, became drunk and all hell broke loose: "Immediately the wedding feast was thrown into confusion, as tables were overturned, and the new bride was violently dragged off by the hair. Eurytus seized Hippodame, and others carried off whichever girl they fancied, or whichever one they could" (Ovid, Met. 12.222-5). Among the men present, Theseus was the first to react: he freed the bride from the Centaurs, and, when Eurytus attacked, he killed the horse-man by splitting open his head with a heavy antique bowl (Met. 12.227-40). An all-out battle ensued in which Theseus sent numerous other Centaurs to their death (Met. 12.341-54). The second example, from the Bible, refers to the vast majority of Gideon's men who lapped water with their tongues, as dogs do, when God decided which men would accompany Gideon into battle against Midian to deliver the Israelites from oppression. Of the ten thousand men with Gideon at the time, only the three hundred who drank by bowing down and bringing water to their mouth with their hands were chosen for the mission (Judges 7:4-7). Back to top. Dante's Tenzone with Forese. Canto 23.115-17 Dante tells Forese Donati that recalling their past life together would weigh heavily on them (23.115-17) because he no doubt regrets the sort of crude, bawdy humor they each expressed so well in a youthful exchange of poems. The tenzone, a literary "dispute" in which the two writers show off by alternately insulting one another, was a popular medieval genre, an early precursor of the verbal dueling heard today in "rap dissing." The combatants usually take a word or an image from the previous poem and use it as a hook upon which to hang a new theme and continue the assault. Thus we find in the six sonnets exchanged between Dante and Forese (3 poems each) the following lowlights: 1a. Dante feels sorry for Forese's coughing wife (perpetually cold in bed): "Her cough, her cold, and all her other fears / are not because she is advanced in years / but only for some lack inside her nest." 1b. The morning after a coughing fit, Forese expects to find pearls and gold coins in a graveyard but instead comes upon an Alighieri--Dante's father?--tied in knots in a graveyard. 2a. Dante picks up on the knot motif to underscore Forese's dissolute ways and subsequent debt: "And mind you, even if you stopped your gluttony / it's now too late to pay back what you owe." 2b. Forese tosses back the poverty theme, countering that "if we're such beggars as you say, / why do you come back right here to beg?" 3a. To which Dante replies by linking Forese's gluttony with criminal behavior: "into your throat so much you have gulped down / you are now forced to steal what is not yours." 3b. Forese finally exploits the fact that Dante's father had financial problems of his own and may have been involved in some shady dealings. He knows Dante is Alighieri's son by the revenge Dante took "against the man who changed his money just the other night." (Dante's Lyric Poems, trans. Joseph Tusiani [Brooklyn: LEGAS, 1992], 109-15) Back to top. "Sweet New Style" (dolce stil novo). Canto 24.49-62 When Bonagiunta da Lucca identifies a dolce stil novo ("sweet new style") as the defining difference between Dante and certain other Italian poets (including Bonagiunta himself: 24.55-62), he raises an issue that has challenged readers and scholars ever since. Is this "sweet new style" attributed to Dante alone or does it apply to a select group of poets, including perhaps the two Guidos, Guinizzelli and Cavalcanti, in addition to Dante? And what, precisely, does Bonagiunta mean by dolce stil novo in the first place? The "style" would seem to bear some relation to the poem cited by Bonagiunta, "Ladies who have understanding of love," as indicative of the "new rhymes" brought forth by Dante (24.49-51). This is one of the most important poems of the Vita Nuova, the story--in a hybrid form of prose and poetry--of Dante's early life (nuovo can mean "new," "young" and / or "strange"), in particular the role of Beatrice from his first sight of her when he was nine years old to her death in 1290 and his eventual resolve (in the final paragraph) to "say of her what was never said of any other woman." The cited poem, the first of three major canzoni (longer compositions) in the book, marks a high turning point in Dante's development as a poet and a lover: he realizes that his happiness--indeed his beatitude--lies not in playing amorous games of hide-and-seek or (worse) wallowing in self-pity but rather in praising his beloved Beatrice. The young Dante will not stay true to this noble sentiment--as the Vita Nuova takes us on an emotional rollercoaster ride--but he occasionally succeeds in spectacular fashion. The sonnet "Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare" ("So gentle and so honest appears") not only conveys the direct, limpid qualities of Dante's "sweet new style" but it captures Dante's conception of Beatrice as a blessed being--and, literally, a "bearer of blessings"--whose greeting (saluto) is intrinsically related to the recipient's salvation or spiritual health (salute): So gentle and so honest appears my lady when she greets others that every tongue, trembling, becomes mute, and eyes dare not look at her. She goes hearing herself praised, benevolently clothed in humility, and seems a thing come down from heaven to earth to reveal miraculousness. She appears so pleasing to whoever beholds her that she sends through the eyes a sweetness to the heart, which no one understands who does not feel it: and it seems that from her lips moves a spirit, soothing and full of love, that goes saying to the soul: Sigh. (Vita Nuova, trans. Dino S. Cervigni and Edward Vasta [Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995], 111-12) Beatrice, Dante explains after announcing her death, is symbolically a nine, the number occurring at key moments in Dante's relationship with Beatrice: as the square of three (the Holy Trinity), the number nine is a miracle. Back to top. Audio "Per te poeta fui, per te cristiano" (22.73) through you I became a poet, through you a Christian Back to top. Study Questions 1. How do the bawdy poems exchanged in life between Dante and Forese Donati relate to Forese's appearance and his interaction with Dante on the terrace of gluttony? See 23.37-133, 24.1-18, and 24.70-97. 2. Dante meets Bonagiunta da Lucca, another Italian poet, on the terrace of gluttony. What do we learn about Dante's own poetry--in relation to that of his peers--in 24.49-63? Back to top. Back to Purgatory main page | |

|