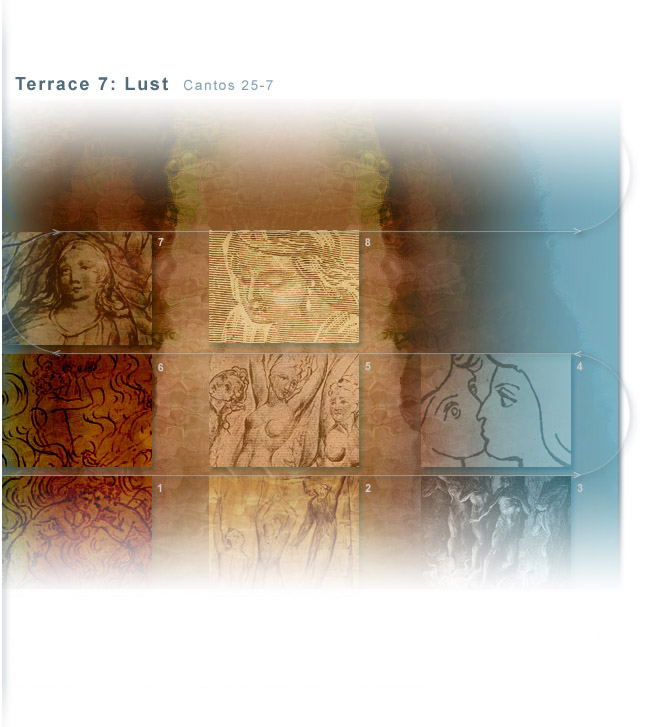

| Terrace of Lust

Encounters: Guido Guinizzelli. Canto 26.91-135 Arnaut Daniel. Canto 26.115-20, 136-48 Allusions: Examples of Chastity and Lust. 25.127-32, 26.40-2 Shades and Shadows. Cantos 25.85-108 Dream of Rachel and Leah. Canto 27.94-108 Gallery Audio Study Questions Home |

|

Terrace of Lust

Climbing to the seventh terrace in the afternoon, Virgil calls on Statius to satisfy Dante's wish to know how shades on the previous terrace (gluttony) can waste away even though they no longer have earthly bodies. Statius replies with a detailed explanation of human physiology and the relation between mortal bodies and the form of the immortal soul in the afterlife. The travelers, now on the terrace of lust, confront flames that extend out from the mountain wall, leaving only a narrow pathway on which to circle the terrace. Dante hears shades inside the fire singing a hymn (calling on God to help calm their lustful passions) and, between verses, shouting out examples of chastity (the Virgin Mary, the goddess Diana) and praising chaste spouses. These souls, whose lust was directed toward members of the opposite sex, are soon met by a second group, guilty of excessive same-sex desire, moving in the opposite direction. After an affectionate exchange of embraces and kisses between members of the two groups, the new arrivals shout out their monitory story (Sodom and Gomorrah) while the first group recalls the sexual liaison between Queen Pasiphaë and the white bull. Among the penitents guilty of heterosexual lust, Dante encounters Guido Guinizzelli, to whom he pays homage as the father of Italian love poetry. Guido points to another poet, whom he calls an even better writer of vernacular verse: Arnaut Daniel, speaking in his native Provençal, courteously introduces himself and asks to be remembered. As daylight fades, an angel, blessing those who are "clean of heart" (the Sixth Beatitude), tells the travelers--to Dante's dismay--that they, too, must enter the flames to reach the next passageway up the mountain. Virgil succeeds in coaxing the terrified Dante through the fire only by reminding him that it separates him from his beloved Beatrice. With night approaching,another angel directs the travelers to the final stairway, but their power to climb quickly ebbs and they lie down to sleep on the steps. Just before daybreak, Dante has a third dream, in which he imagines the biblical sisters Leah and Rachel fulfilling their symbolic roles of action (Leah gathering flowers to make a garland) and contemplation (Rachel looking at herself in a mirror). Dante, Virgil, and Statius reach the top of the mountain in the morning. Here Virgil, in his final spoken words of the poem, proclaims that he has completed his mission by leading Dante through the eternal fire of Hell and the temporal fire of Purgatory. Back to top. Guido Guinizzelli. Canto 26.91-135 Dante considered Guido Guinizzelli (from Bologna) the founding father of the lyric poetry that Dante himself sought to emulate and perfect. Inspired by an ennobling conception of love, such poetry--in Dante's view--was characterized by a beautiful, harmonious style worthy of its subject matter. Guido, whose reputation was already noted by a penitent on the terrace of pride, appears here on the seventh and final terrace of Purgatory purging himself of lust within flames shooting out from the face of the mountain across the pathway. Back to top. Arnaut Daniel. Canto 26.115-20, 136-48 Guido Guinizzelli singles out another poet in his group as the "better craftsman of the mother tongue" (26.117) (audio), a line used six centuries later by T.S. Eliot (as an epigraph to The Waste Land) to honor Ezra Pound. In Dante's poem, this "better" vernacular poet is Arnaut Daniel, a Provençal poet (12th-13th century) praised by Dante for his love poetry and known also for his technical virtuosity (he invented the sestina, in which the same six rhyme words are used in each stanza according to a precise formula). Arnaut's high poetic standing is reflected in the Purgatorio not only through the courtly content of his words but also by the language he uses: this is the only instance in the entire Divine Comedy in which a non Italian character speaks in his "mother tongue" (26.140-7). Back to top. Examples of Chastity and Lust. 25.127-32, 26.40-2 Examples of chastity and lust are provided by the penitents themselves as they walk within a raging fire on the seventh and final terrace of Purgatory. The spirits--at least those who desired partners of the opposite sex--cry out words spoken by Mary at the "annunciation" when she asks how, not having sexual relations with a man (virum non cognosco [I know not man]), she will give birth to Jesus (25.127-8; Luke 1:34). These same spirits then praise the virgin goddess Diana, who upheld the virtue of chastity by expelling one of her nymphs upon learning she was pregnant (25.130-2). Helice (also known as Callisto) was raped by Jupiter (who had gained her trust by posing as Diana) and gave birth to Arcas. Juno, Jupiter's jealous wife, punished Helice by transforming her into a bear. Jupiter later intervened, thus enraging his wife further, by setting Helice and her son Arcas in the heavens as neighboring constellations (Ovid, Met. 2.401-507). This first group of spirits, whose lust was heterosexual, are soon met by a line of shades moving in the other direction. These individuals desired partners of the same sex. After a brief and festive exchange of kisses between members of the two groups, the penitents shout out the cautionary example appropriate to their own lustful desires. Thus the newly arrived spirits, those who lusted for same-sex activity, yell "Sodom and Gomorrah" (26.40), the biblical cities destroyed by fire and brimstone for the transgressions of their inhabitants, including sinful sexual relations between men (Gen. 13:13; 18:20-1; 19:1-28). The other shades meanwhile recall a bestial episode of opposite-sex lust from the classical tradition (26.41-2): Pasiphaë, wife of King Minos of Crete, was inflamed with desire for a handsome white bull. Pasiphaë placed herself inside a fake cow (made by Daedalus) to trick the bull into mating with her. Offspring of this sexual union of woman and bull was the Minotaur (Ovid, Met. 8.131-7; Art of Love 1.289-326). Back to top. Shades and Shadows. Cantos 25.85-108 The Italian word ombra in Dante's lexicon means both "shadow" (as in the shadow cast by a body) and "shade" (a term for the form of the soul in the afterlife). On the terrace of lust, as Dante's very real body prepares for its most challenging test, the poet shows--via a lecture by Statius--how the two meanings of ombra combine to encapsulate the fundamental relationship between life and afterlife. When the soul leaves the body, Statius explains, it "impresses" the body's form on the surrounding air (as saturated air is adorned with colors of a rainbow), and the resulting "virtual" body follows the spirit just as a flame follows fire. This new form therefore goes by the name of "shade" / "shadow" (ombra): as a "shadow" follows--and repeats the form of--a real body, so the "shade" takes on all bodily parts and functions (25.85-108). The word ombra, by exemplifying the relationship between real bodies and their virtual representation after death, points to a basic premise of the Divine Comedy, the reciprocal bond between this world and the hereafter: individuals, through their actions, determine the state of their souls for eternity, while Dante's vision of the afterlife reflects and potentially shapes the world of time and history. Back to top. Dream of Rachel and Leah. Canto 27.94-108 Dante's third and final dream on the mountain of Purgatory is as clear and tranquil as the first two dreams were fraught with violence and (sexual) angst. Having witnessed the painful purgations of all seven terraces (in particular, having experienced for himself the searing heat of lust), Dante now sees in a dream a scene of pastoral calm. Young and beautiful, the biblical character Leah gathers flowers to make into a garland, and she tells how her sister Rachel never stops observing her reflection in a mirror. In their roles of "doing and seeing," Leah and Rachel were conventionally viewed as symbols, respectively, of the active and contemplative lives. (Leah, the first wife of Jacob, bore seven children, while her younger sister Rachel, Jacob's second wife, died while giving birth to her second child [Gen. 29-30, 35].) In the Convivio, his earlier philosophical work, Dante followed the traditional hierarchy, largely based on Aristotle, of contemplation over action: We must know, however, that we may have two kinds of happiness in this life, according to two different paths, one good and the other best, which lead us there. One is the active life, the other the contemplative life, and although by the active, as has been said, we may arrive at a happiness that is good, the other leads us to the best happiness and state of bliss, as the Philosopher proves in the tenth book of the Ethics. (4.17.9) Here in the Divine Comedy Dante's thinking is also influenced by the Platonic-Ciceronian ideal of the philosopher-ruler. Thus the two modes-- contemplation and action, "seeing" and doing"--appear complementary and equally important. For Dante, more so than for many classical and medieval authorities, the life of the mind and the life of the world become one. Back to top. Audio "fu miglior fabbro del parlar materno" (26.117) he was a better craftsman of the mother tongue "per ch'io te sovra te corono e mitrio" (27.142) so that I crown and miter you over yourself Back to top. Study Questions 1. Dante has Statius give a lecture on sex education and shade-making in 25.34-108. What seems to be the relationship between a living human being and its form in the afterlife? 2. On the final terrace, two forms of lust--straight and gay--are purified in a complementary fashion (26.28-42). How does this square (or not) with Dante's treatment of sexual sins in the Inferno (see Inferno 5 and 15-16)? 3. Dante places the terrace of lust closest to the Terrestrial Paradise (Eden) and therefore to Heaven (God): significance? 4. Dante finally "graduates" at the end of canto 27 (127-42). What has he accomplished? What are the implications of this event for Virgil? Back to top. Back to Purgatory main page | |

|