|

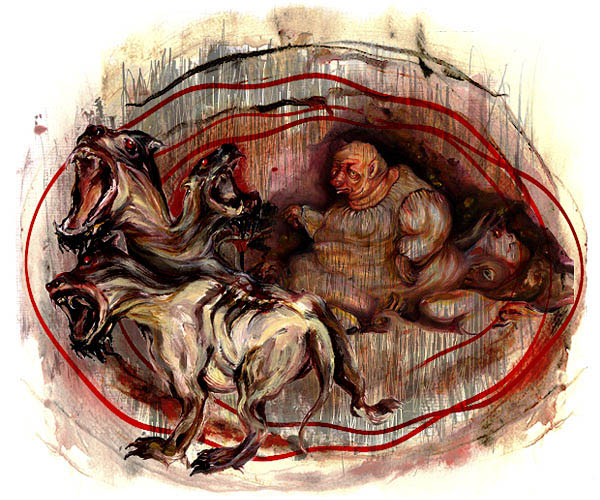

Circle 3 (Gluttony)

Encounters Cerberus, Ciacco Allusions Florentine Politics (1300-2), Last Judgment Gallery Audio Study Questions Home |

|

|

Gluttony Cerberus, a doglike beast with three heads, guards the third circle of Hell and mauls the spirits punished here for their gluttony. The shades, writhing in muck, are unrelentingly pounded by a cold and filthy mixture of rain, sleet, and snow that makes the earth stink. One glutton, nicknamed Ciacco, rises up and recognizes Dante as a fellow Florentine. Ciacco prophesies bloody fighting between Florence's two political factions that will result first in the supremacy of one party (white Guelphs) and then, less than three years later, the victory and harsh retribution of the other party (black Guelphs). After informing Dante that several leading Florentines are punished below in other circles of Hell, Ciacco falls back to the ground, not to rise again until the Last Judgment at the end of time. Gluttony--like lust--is one of the seven capital sins (sometimes called "mortal" or "deadly" sins) according to medieval Christian theology and church practice. Dante, at least in circles 2-5 of hell, uses these sins as part--but only part--of his organizational strategy. While lust and gluttony were generally considered the least serious of the seven sins (and pride almost always the worst), the order of these two was not consistent: some writers thought lust was worse than gluttony and others thought gluttony worse than lust. The two were often viewed as closely related to one another, based on the biblical precedent of Eve "eating" the forbidden fruit and then successfully "tempting" Adam to do so (Genesis 3:6). Based on the less than obvious contrapasso of the gluttons and the content (mostly political) of Inferno 6, Dante appears to view gluttony as more complex than the usual understanding of the sin as excessive eating and drinking. back to top Cerberus A three-headed dog who guards the entrance to the classical underworld. In the Aeneid Virgil describes Cerberus as loud, huge, and terrifying (with snakes rising from his neck); to get by Cerberus, the Sibyl (Aeneas' guide) feeds him a spiked honey-cake that makes him immediately fall asleep (Aen. 6.416-25). Look at Dante's related but very different version of Cerberus in Inferno 6.13-33. How has Dante transformed him to fit the role of guardian in the circle of gluttony? How does Cerberus himself shed light on Dante's conception of the sin? Verses 28-30, describing the actual experience of a dog intent on his meal, exemplify Dante's attention to the real world in his depiction of the afterlife. back to top Ciacco The name "Ciacco"--apparently a nickname for the poet's gluttonous friend--could be a shortened form of "Giacomo" or perhaps a derogatory reference to "hog" or "pig" in the Florentine dialect of Dante's day. Dante, who certainly accepts the common medieval belief in the essential relationship between names and the things (or people) they represent, at times chooses characters for particular locations in the afterlife based at least in part on their names. "Ciacco" may be the first case of this sort in the poem. Independently of what Dante writes in Inferno 6, we unfortunately know very little of Ciacco's life. Boccaccio claims that, apart from the vice of gluttony (for which he was notorious), Ciacco was respected in polite Florentine society for his eloquence and agreeableness. Another early commentator (Benvenuto) remarks that the Florentines were known for their traditionally temperate attitude toward food and drink--but when they fell, they fell hard and surpassed all others in their gluttony. back to top Florentine Politics (1300-2) Spring of 1300 is the approximate fictional date of the journey: we know Dante, born in 1265, is at the "half-way point" of life--age 35 based on the conventional life-cycle of 70 years--when the poem opens (Inf. 1.1). At this time, Florence was politically divided between two rival factions known as white and black guelphs. Ciacco (Inf. 6.64-72) provides the first of several important prophecies in the poem of the struggle between these two groups that will result in Dante's permanent exile from Florence (from 1302 until his death in 1321). The white guelphs--the "party of the woods" because of the rural origins of the Cerchi, their leading clan--were in charge in May 1300, when violent skirmishes broke out between the two parties. Although ring-leaders from both parties were punished by banishment (Dante, a white guelph, was part of the city government that made this decision), by spring of the following year (1301) most of the white guelphs had returned while leading black guelphs were forced to remain in exile. However, the tables were soon turned so that by 1302 ("within three suns" from the riots of 1300) six hundred leading white guelphs (Dante among them) were forced into exile. The black guelphs prevailed because they were supported by Charles of Valois, a French prince sent by Pope Boniface VIII ("one who tacks his sails") ostensibly to bring peace to Florence but actually to instigate the violent overthrow of the white guelph leadership. back to top Last Judgment When Virgil tells Dante that Ciacco will not rise again until the "sound of the angelic trumpet" and the arrival of the "hostile judge" (Inf. 6.94-6), he is alluding to the Last Judgment. Also called the Apocalypse and the Second Coming of Christ, the Last Judgment in the medieval Christian imagination marks the end of time when God comes--as Christ--to judge all human souls and separate the saved from the damned, the former ascending to eternal glory in heaven and the latter cast into hell for eternal punishment. Scripturally based on Matthew 25:31-46 and the Book of Revelation (Apocalypse), this event is frequently depicted in art and literature of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, most famously in Michelangelo's frescoed wall in the Sistine Chapel in Rome. The young Dante would have had ample opportunity to reflect on the Last Judgment from his observation of its terrifying representation on the ceiling of the Florentine baptistery. According to the accepted theology of Dante's day, souls would be judged immediately after death and would then proceed either to hell (if damned) or purgatory (if saved); this judgment would be confirmed at the end of time, and all souls would then spend eternity either in hell or in heaven (as purgatory would cease to exist). The Divine Comedy presents the state of souls sometime between these two judgments. In Inferno 6 we also learn with Dante-character that souls of the dead will be reunited with their bodies at the end of time. The suffering of the damned (and joy of the blessed) will then increase because the individual is complete and therefore more perfect (6.103-11). back to top Audio "più non ti dico e più non ti rispondo" (6.90) I tell you no more and I no longer answer you back to top Study Questions 1. Describe the contrapasso--the relationship between the vice and its punishment--for gluttony. 2. Look at lines 57, 76, and 90. How might Dante figuratively participate in the vice of gluttony? back to top Back to Inferno main page | |

|